By Amy Gardner

Washington Post February 11, 2022

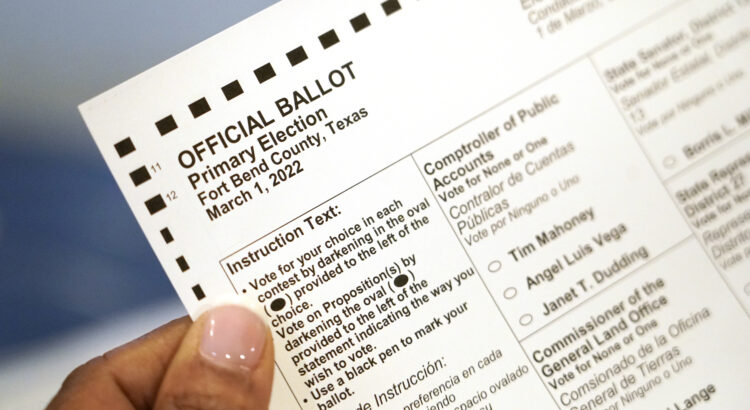

A restrictive new voting law in Texas has sown confusion and erected hurdles for those casting ballots in the state’s March 1 primary, with election administrators rejecting early batches ofmail ballots at historic rates and voters uncertain about whether they will be able to participate.

In recent days,thousands ofballots have been rejected because voters did not meet a new requirement to provide an identification number inside the return envelope.

In Harris County, the state’s most populous county and home to Houston, election officials said Friday that 40 percent of roughly 3,600returned ballots so far have lacked the identification number required under Senate Bill 1, as the new law is known. In Williamson County, a populous northern suburb of Austin, the rejection rate has been about 25 percent in the first few days that ballots have come in, the top election official there said.

“Twenty-five percent of mail ballots from the starting blocks is a big deal for our county,” said Chris Davis, Williamson County’s elections chief. “We’ve never seen it before. And yes, our hope is that we can get these voters to correct the defects in a timely fashion. But what if they don’t, because three months ago they didn’t have to? There’s a learning curve. There are going to be possibly painful lessons that their vote doesn’t count because they weren’t aware.”

All the officials said that the sample size is small at this early stage and that the rate of rejected ballotscould improve as more arrive. Jennifer Anderson, the elections chief in Hays County, southwest of Austin, said her staff had rejected 25 percent of the first small batch of returned ballots — but by Friday morning, the rate had dropped to 4 percent.

“It seems like our outreach is working,” she said.

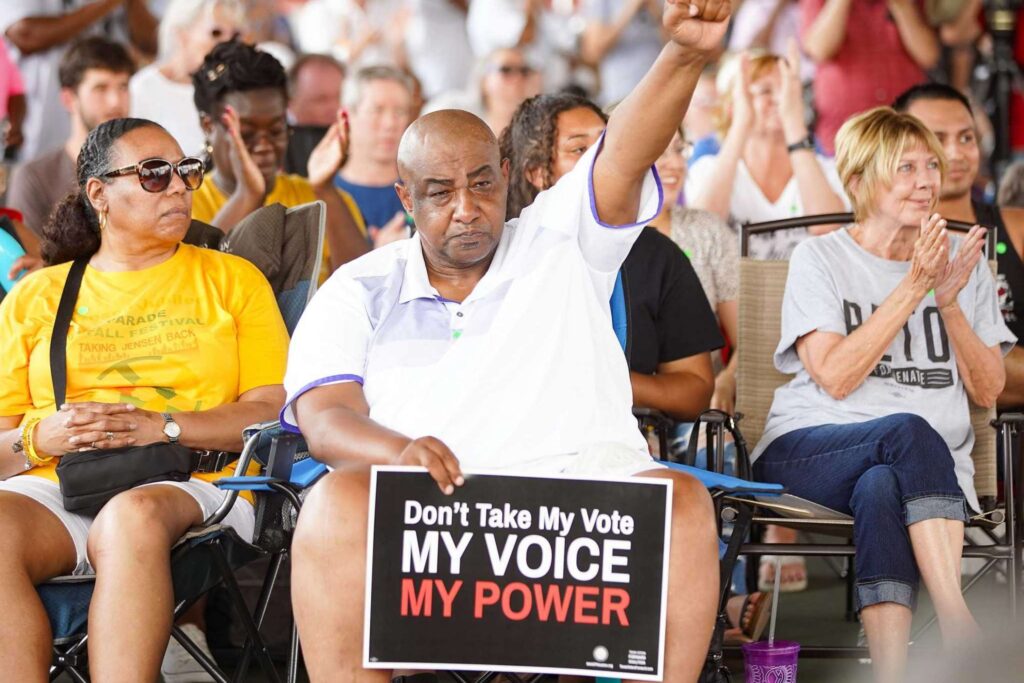

Still, the defect rate so far is alarming election administrators, voting advocates and some voters as primary day quickly approaches and many thousands more ballots are still to be returned. The rejection rates provide an early opportunity to assess the impact of Senate Bill 1, one of dozens of restrictive voting laws enacted by Republicans across the country last year amid an avalanche of false claims, many from former president Donald Trump, that the 2020 presidential race was tainted by widespread fraud.

State Rep. Briscoe Cain (R), a leading proponent of Senate Bill 1, said in a text message that “Texans deserve to have confidence in the electoral system.” The new law ensures that, Cain said, by creating uniform voting hours across the state, expanding access for those who need assistance and enhancing transparency with provisions that protect the rights of partisan poll watchers.

“I’m confident that local election officials will prioritize assisting voters through the process instead of gaslighting to gin up fear and confusion,” Cain said.

In addition to adding identification requirements, the wide-reaching law imposes new penalties for anyone who registers to vote or casts a ballot but is not eligible to do so. It also empowers partisan poll watchers by imposing penalties on poll workers who impede their ability to observe the voting process, among other changes.

A federal judge delivered a narrow defeat to one part of the law on Friday. U.S. District Judge Xavier Rodriguez ruled that in Harris County and in the Austin area, the state can’t enforce a provision forbidding public officials to encourage voters to vote by mail, the Associated Press reported. Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s office did not immediately respond to a message.

The rejection of mail ballots is not the first challenge that Senate Bill 1 has presented, and election officials — who are nonpartisan in Texas — fear it won’t be the last. In January, counties also began rejecting a high percentage of mail ballot applications, which now require the same identification numbers as the ballots themselves. The law requires voters to provide either a Texas state identification number, typically from their driver’s license, or the last four digits of their Social Security number. The number they provide must match the identification number on file with their registration record.

Many counties are experiencing significant application rejection rates; in Harris, the figure is 35 percent to date, officials said.

In Texas, mail-in voting is open only to those who are over 65, will be away from home on Election Day or have a disability that prevents them from voting in person. Mail voting has for decades been the province of Republicans, who developed robust outreach programs and in many states championed legislation allowing the practice. In 2020, however, when Trump criticized mail balloting as an opportunity for fraud, many GOP voters began shunning the practice.

“It feels like people were just sitting up late at night thinking up ways to discourage people from voting,” said Jo Nell Yarbrough, a 76-year-old retired educator from Katy, Tex., west of Houston, who received a letter early this week from her local election office informing her that she had neglected to include an identification number on her application for a mail ballot.

Yarbrough sent out the application a second time and said she is optimistic that she’ll get the ballot in time to vote and mail it back again — and she is also willing to vote in person if necessary, once early voting begins Monday. But Yarbrough, a Democrat, said she fears that others might not be so persistent.

“It’s just making another hurdle for people,” she said. “And many people are going to give up and say, ‘I don’t feel like doing this or that.’ Not that it’s not worth it, but when you get older, you don’t want hassles.”

The GOP-controlled Texas legislature and Gov. Greg Abbott (R) enacted Senate Bill 1 in early September after Democrats tried unsuccessfullyto halt the bill bydenying Republicans a quorum in the House for months.The law went into effect in December despite entreaties from county election officials to give them more time to educate their staffs and voters. Lawmakers also denied local officials’ requests to push back the primary date.

As a result, election administrators have been scrambling to understand the new rules, procure new materials such as ballot requests and voter registration forms required under the law — and teach the public how it will affect them. They have relied on guidance from the secretary of state’s office, which in some cases has taken months to develop.

That fueled the confusion about how to process mail-in ballot applications, said Remi Garza, the elections chief in Cameron County, at the state’s southern tip.

“There was a lot of information that had not been distributed to all the 254 counties in Texas, so different administrators had different levels of information with respect to how you could process these applications,” said Garza, who leads the Texas Association of Elections Administrators.

That delay also contributed to a shortage of voter-registration cards as organizers with groups such as the League of Women Voters were unsure whether they could use their stockpiles of old cards or would have to wait to receive new forms from the state. The new form explains Senate Bill 1′s increased penalties for anyone providing false information on their voter registration application.

State officials told League organizers that they would not be able to provide the tens of thousands of registration cards they normally supply because of a nationwide paper shortage and rising costs.

Nancy Kral, an officer with the Houston chapter of the League of Women Voters, said the state’s top election official, Keith Ingram, told her during a telephone call that the state was not going to continue “subsidizing” the League’s registration efforts. The League provides voter registration cards to every participant in naturalization ceremonies in Houston — about 45,000 applications since June 2020.

A spokesman for the office of the secretary of state did not immediately respond to a request for comment on that exchange. But the spokesman, Sam Taylor, said the office has tried to inform election officials about all the changes. “Our office has been working as quickly and diligently as possible within a compressed time frame to provide guidance to both election officials and voters on changes to the voting process in Texas,” he said in an email. “Our goal from day one has always been to make sure that all eligible Texas voters can successfully cast a ballot, and that remains our goal going forward.”

Officials finally gave guidance — in either late December or early January, according to Taylor — that the old registration cards would be accepted this year. The deadline to register in time to vote in the primary was Jan. 31.Officials also provided more forms after the League threatened to sue under the National Voter Registration Act, which requires states to provide voter registration forms to third-party groups.

The new law is the target of multiple ongoinglawsuits, including one filed by the League of Women Voters, arguing that it violates the law by restricting voting access.

Kral has been disheartened by the hurdles Senate Bill 1 has erected — as well as the tone it seems to have set, she said. “It’s just so complicated and confusing,” she said. “There’s a perception that the confusion is not only in the name of election integrity but also about influencing who feels comfortable voting. I don’t think they’d admit to that, but that’s the message I’m receiving. They’re bullying.”

The late guidance from the state, as well as the paper crunch, has created stress for election officials, too. Garza, in Cameron County, described having to wait for instructions on the new mail-ballot envelope requirements before he could place his order. The new identification requirements necessitated an envelope redesign that includes a large privacy flap to cover the box where voters must provide their identification number.

Garza said his envelopes had still not arrived last week, when counties were supposed to begin mailing ballots to eligible voters. So on Saturday, he sent three of his staff members on a four-hour road trip to San Antonio, where a local printer had the envelopes in stock.

“We put them in the mail on Monday, and through the cooperation of our local postmaster, the voters began to receive them in their mailboxes today,” Garza said Wednesday. “That’s at least a week and a half later than we would have liked.” And it gives voters that much less time to fix any errors or omissions on their ballots, he added.

Several election administrators said they are optimistic that the rejection rate for both ballots and ballot applications will continue to decline as more come in — and as they get the word out to the public about the new rules.

But they are braced for another source of confusion, which is Senate Bill 1′s new penalty for poll workers who impede the ability of partisan poll watchers to observe voting locations on Election Day.

Davis, the top elections official in Williamson County, said the law has had a chilling effect on his ability to recruit poll workers, who have told him they worry that any effort to maintain order or protect voter privacy could be construed as a violation. But he also said he is optimistic that new mandatory training for poll watchers and poll workers will clarify what is acceptable behavior and what is not.

“Poll watchers are not our enemy — at least they’re not supposed to be our enemy,” Davis said. “The problem up until now is that in a poll watcher’s quest to see irregularities, they may not have had a terribly firm grasp on the ‘regular’ — how things are supposed to run in a polling place.” The training should improve that, he said.

Cain, the Republican lawmaker, said the new law “has ample protections for partisan election judges in dealing with disruptive election observers.”

Several election administrators said clashes between watchers and workers will be less likely on March 1, because it is a primary election. The real test of the new poll watcher rules will come in the general election in November, they said.

That’s just fine with Garza, who believes that voters — and election administrators — have enough to get used to right now.

“Elections are robust,” Garza said. “But they’re also very delicate. People need to mindful of how much things have changed since the last election. That’s what’s keeping me up at night.”