US News Reporter

Republican officials in Ohio and Virginia have sparked controversy by removing thousands of voters from their state’s electoral roles ahead of elections in November, with one campaigner accusing the GOP in Virginia of a “direct attempt to blatantly disenfranchise voters.”

In Ohio, 26,000 voter registrations deemed inactive by Republican Secretary of State Frank LaRose were removed ahead of a crunch vote seeking to enshrine abortion access in the state’s constitution. It came after LaRose wrote to local boards of elections in June, instructing them to terminate the registrations of voters who had been inactive over the past four years.

Those removed hadn’t voted since May 2019 and failed to respond to letters from local authorities asking them to confirm their voter status. LaRose said this was done carefully to avoid disenfranchising genuine voters and said 12 people had replied to letters sent out stating they still want to be registered in Ohio.

He commented: “The last thing we want to do is unnecessarily remove someone from the voter rolls, and that’s why we’re so careful about this.”

The process was challenged by Jen Miller, executive director of the League of Women Voters of Ohio, who accused LaRose of “using a hatchet.” Speaking to The Columbus Dispatch, she said: “They get two notices in the mail that are written in arcane legalese and often don’t make sense to voters.

“So this process is just incredibly ineffective. It’s like using a hatchet rather than a surgical blade to make sure that we’re only removing those individuals who have passed away or moved out of state.”

Democratic state Representative Bride Rose Sweeney has written to LaRose demanding clarity over the disenfranchising process.

In a statement sent to Newsweek, LaRose said: “When it comes to maintaining our voter rolls, we don’t quietly ‘purge’ active voters. We remove inactive registrations after we’ve learned a voter has moved and not been active at the address for more than four years. That’s been the federal law for three decades, and it’s essential to keeping out rolls honest by eliminating duplicate registrations.”

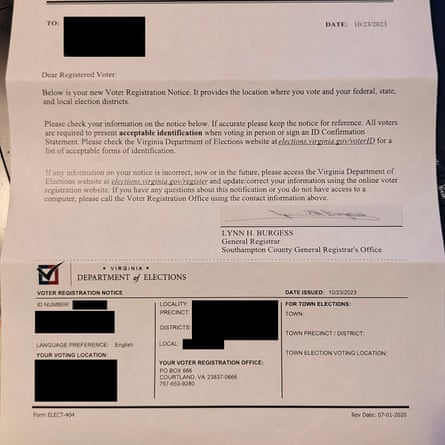

Separately, Democrats in Virginia are calling for a Department of Justice investigation after thousands of voters were mistakenly removed from electoral rolls. On Friday, officials working for Governor Glenn Youngkin admitted 3,400 voters had been taken off the rolls due to a computer software error.

However, not everybody buys this explanation. Nick Gothard, the election protection manager of the Virginia Civic Engagement Table nonprofit, told The Hill that the move was a “direct attempt to blatantly disenfranchise voters.”

He added: “These incidents, occurring in such close proximity to election day, raise serious questions about ongoing voter suppression tactics and efforts to subvert public trust in Virginia’s secure and fair elections.”

On Monday, Virgina’s two Democratic senators and six House representatives wrote to the Department of Justice urging “immediate action” to investigate why the voters were removed.

The Virginia elections department said it is “worked diligently [with State Police] to review and check each canceled record to ensure all impacted voters are reinstated.”

Newsweek reached out to Governor Youngkin for comment via email.

It comes amidst growing concern over alleged voter suppression across the United States. Speaking to Newsweek, David Bateman, an expert in democratic institutions at Cornell University, attributed this primarily to Republicans.

“Voter suppression tactics have become increasingly common in recent decades, especially now that the Voting Rights Act has been eviscerated by the Supreme Court,” Bateman said. “The Republican party is, by far, the most active culprit here, and have made voter disenfranchisement a central component of their political campaign strategies.

“There are a few very straightforward reasons for this. The Democratic party traditionally relied heavily on mobilizing working-class voters. Higher barriers to voting disproportionately affect working-class people. As a result, Republicans look to suppress voting, and Democrats look to expand it,” he said.

Bateman said this has not been a particularly effective tactic.

“The one piece of good news is that, to date, most voter suppression efforts have been relatively ineffective,” he said. “Again, there’s a few reasons for that. The voters these target are not likely to turn out in the first place. The forms of suppression can be countered by organizing, including voter registration drives and legal challenges.

“This is a resource drain for Democrats and voting rights organizations, so it’s still costly even if there isn’t a clear effect at the polls. And the forms voter suppression has taken to date are limited by state and federal jurisprudence.”

Faith in election integrity among some Republicans has been undermined by Donald Trump‘s repeated claim that the 2020 election was stolen from him by voter fraud. This claim has been repeatedly rejected in court and by independent election and legal experts.

Update 11/2/23, 11:56 a.m. ET: This story has been updated with comment from Ohio Secretary of State Frank LaRose.