By Jesse Wegman

For those who spend their days operating within the constraints of empirical reality, the long-running voter-fraud scam peddled by right-wing con artists poses a dilemma: Respond to their claims and give them the veneer of legitimacy they crave. Ignore them, and risk letting transparent lies spread unchecked.

I used to err on the side of responding as often as possible, in the belief that persistent fact-checking and debunking was the best way to inoculate the American public against a virulent campaign of deception. But it became clear to me, probably later than it should have, that this was always a fool’s game. The professional vote-fraud crusaders are not in the fact business. While they pretend to care about real election crimes, their purpose is not to identify whether voters are actually committing such crimes; it is to concoct a world in which the votes of certain people (and it always seems to be the same people) are presumptively invalid. That’s why they are not chastened by data demonstrating — again and again and again and again — that there is essentially no voter fraud anywhere in this country.

Thanks to their efforts, about three quarters of Republicans believe the 2020 election was stolen, and they won’t be convinced by evidence to the contrary.

That evidence continues to grow. Earlier this week The Associated Press released an impressively thorough report examining every potential case of voter fraud in six decisive battleground states — Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin — where Donald Trump and his allies challenged the result in 2020. Voters in these six states cast a combined 25.5 million votes for president last year, and chose Joe Biden over Mr. Trump by 311,257 votes. The total number of possible cases of fraud the A.P. found? Fewer than 475, or 0.15 percent of Mr. Biden’s margin of victory in those states.Many of those cases the A.P. identified turned out not to be fraud at all. Some involved a poll worker’s error or a voter’s innocent confusion, such as the Trump supporter in Wisconsin who mistakenly thought he could vote while on parole. (“The guy upstairs knows what I did,” the man said after a court appearance. “I didn’t have any intention to commit election fraud.”)

In the few instances of clear fraud — for example, a Pennsylvania man who cast two ballots, one for himself and, later in disguise, one for his son — local authorities were quick to act. In Arizona, officials investigated 198 cases of potential fraud, most involving double-voting. They invalidated virtually all of the second votes and have so far charged nine people with voting fraud crimes.

That’s the thing about voter fraud: Not only is it rare, it’s generally easy to catch, especially if it happens on a larger scale. In 2019, North Carolina officials ordered a do-over of a congressional election after the winning candidate’s campaign was found to have financed an illegal voter-turnout effort. That candidate was a Republican, as were two of three residents of the Villages, a Florida retirement community, who were arrested and charged with double voting in the 2020 election earlier this month. (The third had no party affiliation.)

Given how much Republicans bang on about the dangers of voter fraud, a little schadenfreude is in order here. But it misses the bigger point: To the extent there is any fraud, it is almost entirely an individual phenomenon. The A.P. report confirmed this, finding no evidence anywhere of a coordinated effort to commit voter fraud. That’s no surprise. Committing a single case of fraud is hard enough; doing so as part of a conspiracy is essentially impossible, once you consider how many people would need to be in on the scheme. “It’s a staggeringly inefficient way to affect an outcome,” said David Daley, the author of “Unrigged: How Americans Are Battling Back to Save Democracy.” “It simply doesn’t work.”

To sum up once more for the folks in the cheap seats: Voter fraud is vanishingly rare. It is virtually never coordinated. And when it does happen, it is often easily discovered and prosecuted by authorities.

I hold no illusions that any of these truths will matter to those who have invested themselves in tales of widespread fraud. After all, they weren’t moved when both Republican and Democratic officials in states around the country reaffirmed, in some cases multiple times, the accuracy and integrity of their vote counts. Even Bill Barr, the former attorney general and one of Mr. Trump’s most reliable bootlickers, could not bring himself to repeat the lie that there was any meaningful fraud in 2020.

Alas, Republican voters don’t listen to Bill Barr. They listen to Donald Trump, who dismissed the A.P.’s report by doing his standard Mafia don impression. “I just don’t think you should make a fool out of yourself by saying 400 votes,” the former president told the news organization, insisting that the true number of fraudulent votes in 2020 was in the “hundreds of thousands.” His evidence? An unreleased report by a source he refused to name.

This is how it goes with the vote-fraud fraudsters. The damning evidence is always right around the next corner, or the one after that. Recall that Mr. Trump established a voter-fraud commission soon after he entered office, with the goal of rooting out the supposedly massive fraud that led him to lose the popular vote by nearly three million votes. (Like everyone else, he knew that true democratic legitimacy comes not from the Electoral College, but from a majority of the American people.) The commission was led by Kris Kobach, the indefatigable vote-fraud warrior whom Mr. Daley once called “an Inspector Clouseau who gazes into his mirror and sees Sherlock Holmes.” In Mr. Kobach’s previous job as Kansas’s secretary of state, he spent years hunting for widespread vote fraud and won only nine convictions, most of them of older Republican men who had double voted. Under Mr. Kobach’s leadership, the Trump voter-fraud commission disbanded after less than a year of chaos and controversy, without having made any findings.

That’s because, as the A.P. report affirms once again, there was nothing to find. American voters aren’t cheating, and certainly not in any coordinated way.

And here lies the deepest irony of this strange, fragile moment we are living in. A very real threat is, in fact, looming over America’s electoral integrity. But it’s not coming from voters; it’s coming from the people braying the loudest about the importance of election integrity.

Donald Trump turned fact-free charges of voter fraud into an art form, but the exploitation of the predictable public fear generated by that sort of rhetoric has been a central feature of the Republican playbook for years. Back in 2013, the then-North Carolina lawmaker Thom Tillis explained why Republicans in the Legislature were passing their strict voter-ID law. “There is some evidence of voter fraud, but that’s not the primary reason for doing this,” said Mr. Tillis, now a U.S. senator. “There are a lot of people who are just concerned with the potential risk of fraud.” Why are they so concerned? Because their leaders have been feeding them a steady diet of lies.

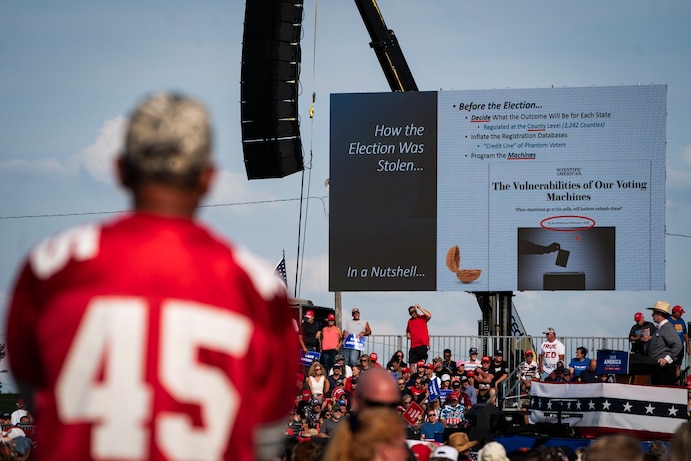

That diet became an all-you-can-eat buffet in the Trump years, culminating in the “Stop the Steal” rallies after the 2020 election and then, horrifically, in the Jan. 6 riot at the U.S. Capitol. Now the same people who subscribed to the lies about election fraud are running for, and often winning, jobs overseeing the running of elections across the country. They are representative of a new generation of Republicans, raised in the fever swamps of Fox News and other purveyors of disinformation, who believe elections are valid only when their candidate wins.

The goal of the voter-fraud brigade, it turns out, was never to identify fraud that might have happened in the past; it was to indoctrinate voters with the terror of stolen elections, and to pave the way for a hostile takeover of American democracy in the future.